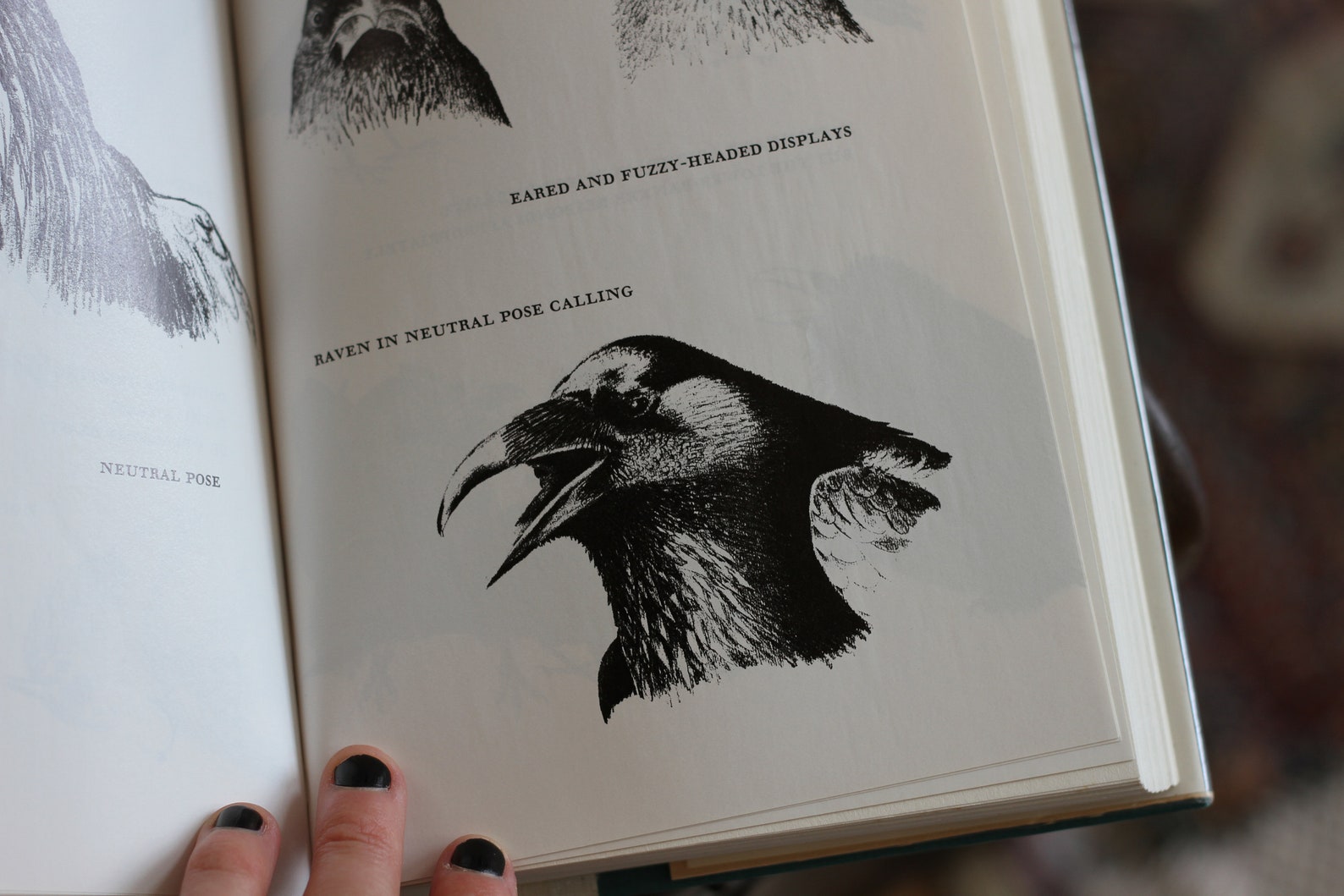

Heinrich freely shares the glimmerings of real understanding he has made-much the same way as ravens share food finds (in apparent, and typical, anti-evolutionary spirit)-including the exploratory/carnal fixation the raven has with bijouterie, and how many ravens it takes to fish the Yellowstone River for cutthroat. Yet here is also a bird that can sit down at the table, to a nicely fatted calf, say, with wolves and golden eagles, animals that are known to serve raven when the calves are scarce. Here is a bird that willingly incubates eggs that are obviously not its own, the smart guy falling for the oldest parasitic trick in the book. He has come away with an admittedly incomplete if anecdotally rich picture of the bird, one that bears up the historical image of a canny creature that trumps our expectations. What makes ravens tick, or, if you prefer, quork? What fires their love of baubles, their delight in tomfoolery? Why have so many cultures portrayed the birds as creators and destroyers, prophets and clowns and tricksters? Are they sentient? Do they scheme? To what use do they put that sizable brain? Heinrich has shared a lot of forest time with ravens over the years, trying to gain perspective on these questions.

of Vermont The Trees in My Forest, 1997, etc.) continues his investigations into the big crow’s behavior. Still wild about ravens after all these years, award-winning zoologist Heinrich (Univ.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)